Ballincollig, Co. Cork

Neil Hegarty, Senior Executive Architect, Cork County Council

1982 – 1985

Photographs – Neil Hegarty (3–6) and Shane O’Toole

“When I joined the County Council in 1975 my first project was in Ballincollig,” says Neil Hegarty. “I spent three months walking around out there looking for ideas. It was a massive flat field, probably part of the original flood plain of the River Lee. The Royal Gunpowder Mills were there. It had also been where the cavalry trained. The wide open spaces were ideal for practising manoeuvres.

“Then they decided to allocate me to the western area of the county. The county was divided into three – north, south and west, each with an assistant manager.” Michael Conlon was the County Manager, the youngest ever and one of the greatest, appointed in 1960 when only 33. He promoted industrialisation. Seeing the need to build houses for the inflow of workers, he set about creating a series of dormitory towns around Cork city. Beginning with Ballincollig, a few miles west of the city boundary, he fast-tracked the building of housing estates around the old village that once played a role in the Napoleonic wars by manufacturing gunpowder. Under his plan, the sleepy hamlet of a few shops and pubs rapidly became Ireland’s fastest growing town, and the largest in Cork by 2016.

“I was moved back from west Cork to south Cork in 1982. It was by far the biggest area, stretching from Bandon to Youghal. I regretted being moved out of west Cork, my favourite place in the world. I was asked to build big housing schemes then. I was happy to get back into Ballincollig, where there was still nothing. But it was a challenge: more than 200 houses in a single scheme, and after what I had been saying during my time in west Cork…? [BOTM February 2020] So now I was designing the largest scheme I tackled – even though I had been preaching small is beautiful for six years! Architects should resign their commission when their client requests something to which they are opposed. But it’s difficult to resign your position from the public sector.

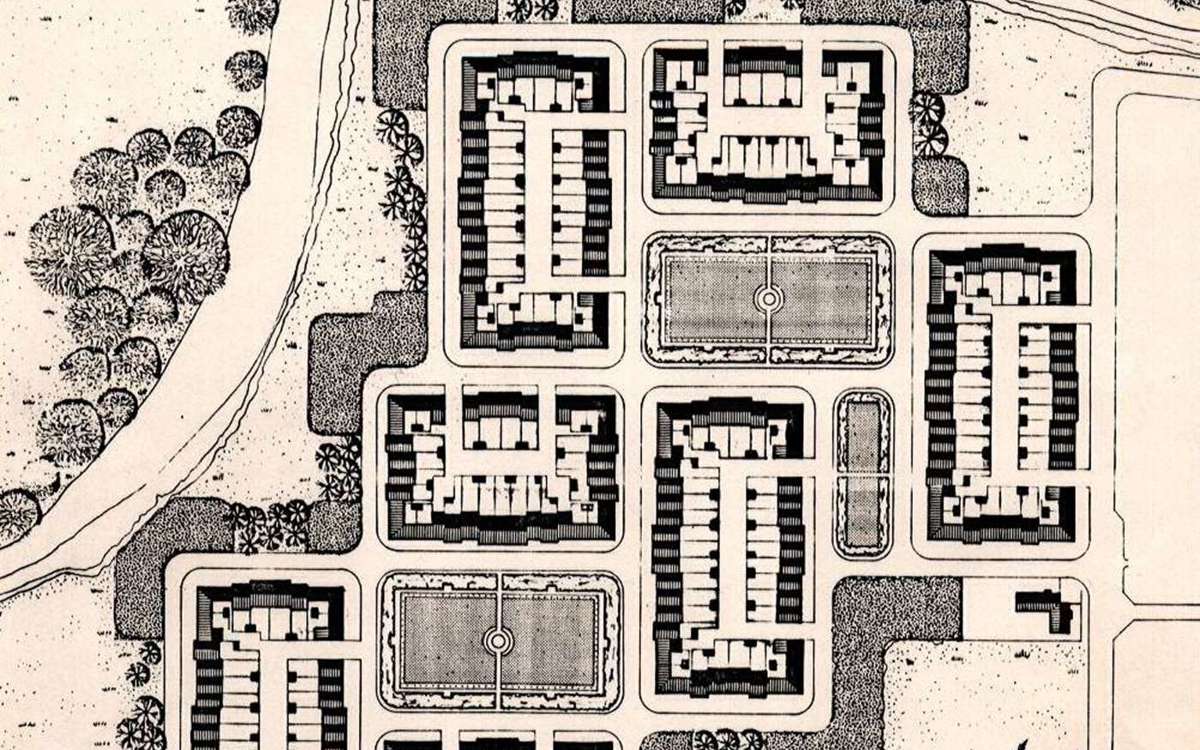

“One of my ambitions for Ballincollig was to get rid of the cars,” he says. “That was one of the first things I thought about, so I grouped them all together within the back gardens, so that the fronts would be okay. I was thinking of the two places I regularly visited in Dublin then – Merrion Square for monthly RIAI council meetings, and Belgrave Square, Monkstown, where my brother Frank lives, and how they worked. I was also trying to give the advantage of the semi-d, with direct access to the garden without going through the house. Then there was the wind. People were saying, ‘This is a place where you’d get pneumonia’. It was a huge flat area, exposed to the westerly wind. I arranged the houses to protect the gardens. I put mounded landscaping into the corners to stop the cold moving up the street and not be a wild windy place.” The scheme comprises seven blocks of two different types, arranged around three local greens, all aligned.

Materials new to the market were used – Forticrete fair-faced concrete blocks and Coratone fibre-cement. “The short corrugated sheets no longer had the aesthetic of agriculture or industry,” says Hickie, “and they had a grander scale than slates, which seemed too domestic for the clubhouse, surrounded as it was by semi-detached houses.”

“We worked a lot through models,” recalls Hickie. Flemming Rasmussen, who had worked for Liam McCormick on St Michael’s Church, Creeslough in 1970-71, made this model. One can’t help but sense some affinity of interests between the clubhouse and McCormick’s later tent-like churches at Glenties (1971-74) and Steelstown (1975-76). Perhaps there was something in the air, but raking columns were first made explicit in Irish architecture at St Mary’s.

Of course there are indirect sporting precedents to be found in the works of Pier Luigi Nervi, particularly his Palazzetto dello Sport, built for the 1960 Rome Olympics. But those were circular forms, based on compression rings, and I prefer the rugby metaphor at St Mary’s of leaning in, scrum-like – alright, an uncontested scrum, if you prefer – with the inclined, straining, structural elements propped by pillars well hidden from the punter’s view.

The 21 different house types means there are no north-facing living rooms and no south-facing kitchens. Precise modular coordination means there are no cut bricks. There are only five basic window types throughout. Pipework was designed to eliminate the need for boxing in. Staircases were simplified. Eaves feature a combined wall plate and window lintel of tanalised timber. This sort of relentless drilling down permitted the specification of full-brick fronts from Castlemore, and front boundary walls designed to double as planters. One of the most interesting aspects was the building of a local estate office, funded by the County Council, the Southern Health Board and the building contractor and material suppliers, who gave labour and materials at cost. This was the first attempt in the country at providing for the management of an estate locally.

“We need architecture to build community, not for itself,” says Hegarty. “The first group of tenants in Ballincollig were great. I talked with them about the philosophy of the project. Then when the government brought in a £5,000 grant to encourage tenants to move out of local authority homes, it emptied the best people out of every scheme. Ballincollig became open to vandalism then. The first tenants were very good. I think the landscaping would have survived. Those were the knock-on effects of not realising that they had been overbuilding. But there is one other nice thing I remember about Innishmore. When I was about to move to Cork City, in 1985, the late Pat Dowd, Cork County Manager then, was overheard to say after a visit: ‘Neil Hegarty is leaving us a present’.”

A spin-off scheme, Brook Lodge Square, was built at Glanmire, later in the 1980s, after Neil had left for the Corporation. Neil wishes to acknowledge two architects, without whom Innishmore would not have happened: project architect – now Cork City Architect – Tony Duggan and Gus Cummins, the former Principal Advisor (Housing Division) at the Department of Environment and Local Government.